Due to the increasing demand for electric and electronic equipment (EEEs), high-purity silver remains in high demand. For the past few years, silver demand has exceeded silver mining production, but the global supply has nearly met the demand each and every year – thanks to silver recovery and silver refining. Silver recycling will also be critical to meet future demand, especially as we see the general demand for metals increase across the globe in relation to technological growth. High-purity silver can be produced from silver refining and silver recycling by utilizing a series of methods and processes, such as silver electrowinning and electrorefining. I’d like to delve into how these processes are carried out, and the outlook for silver production.

The Value of Silver

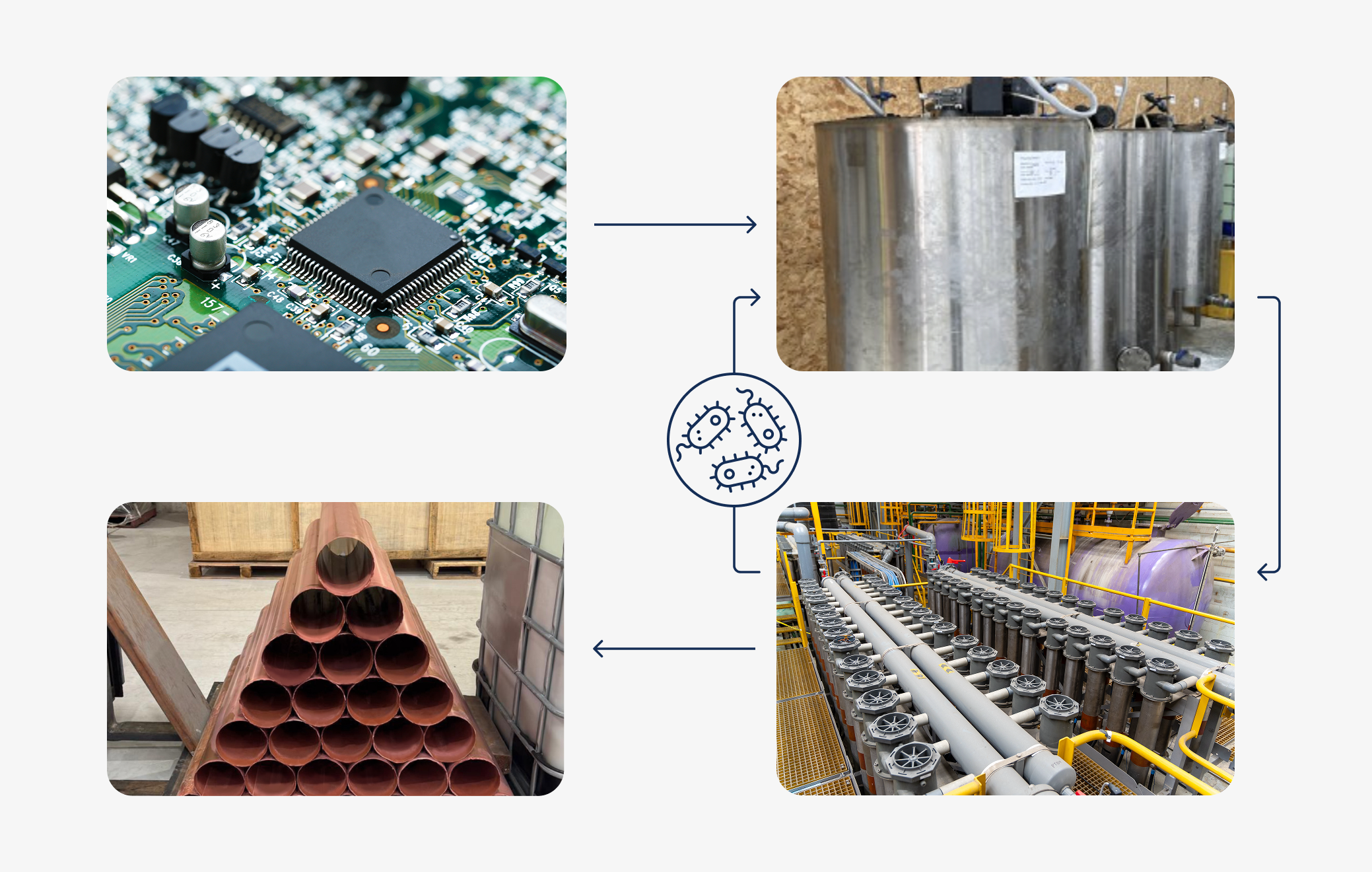

Silver has a variety of uses, ranging from jewelry and silverware to electronics and renewable energy. As a catalyst, silver is used in the production of two major industrial chemicals: ethylene oxide and formaldehyde. Silver is also a large component of photovoltaics; the solar panel industry consumed 29% of the total industrial demand in 2024.1 According to the World Silver Survey 2025, annual consumption for the industry has reached nearly 200 million ounces.2 Because of its high conductivity, silver is widely employed in electric and electronic equipment, which includes, but is not limited to: printed circuit boards (PCBs) in phones, computers, and TVs; in membrane switches used in buttons; and in devices like RFID tags. Although small amounts of silver are required in these devices, it still makes up a relatively large percentage of the monetary value in relation to the actual amount used. It’s because of this that many of these devices are recycled, and a lot of research and effort goes into these processes. Silver ores usually contain a very low content of silver, which is why a lot of methods have been developed to extract silver from electronics.

Production of High-Purity Silver

In 2024, 819.7 million ounces of silver were mined, out of the year's total supply of 1,015.1 million ounces. The primary source of silver remains production from various ores, with 27.8% recovered from primary silver mines, while the remaining 72.2% is recovered as a by-product of other metals, specifically lead/zinc (29.4%), copper (26.8%), and gold (15.5%).2

Silver Refining and Silver Recovery Methods

Copper Concentrates

Copper sulfide concentrates are smelted, resulting in blister copper, which contains approximately 97-99% of the silver that was in he origal concentrate. The blister copper is then electrolytically refined and ‘slimes’ accumulate on the anode or at the bottom of the refining tank. These slimes contain insoluble impurities, like silver. The slmes are collected and smelted, oxidizing all the metals except for gold, platinum group metals (PGMs), and silver. The metal that is recovered is called doré, which typically contains 0.5-5% gold, 0.1-1% PGMs; with the balance as silver. The doré metal is cast into anodes and electrolyzed in nitrate solution to obtain high-purity silver.

Gold Concentrates

Cyanide leaching is often used to recover gold from its ores. Fine gold particulates dissolve easily in cyanide, typically using NaCN concentrations of 0.02-0.05%; if the dissolved oxygen content of the solution is not high enough, aeration may be required.

4 Au + 8 NaCN + O2 + 2 H2O → 4 NaAu(CN)2 + 4 NaOH

Once dissolved in the cyanide, the gold must be recovered from the pregnant cyanide solution. Often, the Merrill-Crowe zinc precipitation process is used, or the adsorption of gold onto activated carbon.

The steps in the Merrill-Crowe process are oxygen removal, mixing in of fine zinc powder, and gold precipitate recovery by filtration. The addition of zinc leads to the formation of a zinc cyanide complex and gold metal.

2 Au(CN) + Zn → 2 Au + Zn(CN)42-

Sulfuric acid is used to dissolve any zinc impurities that have precipitated with the gold. The final gold solids are smelted into a gold doré bar.

Silver is also easily leached using cyanide, and can be recovered using the same methods employed for gold recovery, as described above. However, electrowinning has proven to be an economical alternative, even more so when utilizing emew technology. Electrowinning can be used directly after the cyanide leach, resulting in fewer process steps, and, therefore, lower operating costs.

Lead Concentrates

Lead sulfide concentrates are roasted and smelted to form lead bullion. The various impurities, including antimony, arsenic, silver, and tin, are removed by various processes; silver is removed by the Parkes process. In this method of liquid-liquid extraction, zinc is added to a molten lead/silver mixture and cooled slowly. Because of zinc’s high melting point and lower specific gravity, it solidifies before the lead. The silver in the mixture becomes concentrated in the zinc crust, since it is 3000 times more soluble in zinc than in lead. Gold also reacts with the added zinc, and this gold-silver-zinc alloy is easily drossed off the liquid lead. The remaining lead-gold-silver residue is treated by cupellation, the process of heating to high temperatures (>800ºC) under strongly oxidizing conditions for impurity removal. First, the antimony, arsenic, and zinc are oxidized and removed, followed by lead, with bismuth, copper and tellurium being the last to be oxidized and removed as a slag known as “copper litharge”. The remaining gold-silver alloy typically has a 99.9% purity. To separate the gold from the refined silver, a process known as ‘parting’ is used. The most commonly employed method is the digestion of the alloy with nitric acid, wherein the silver is dissolved, the remaining gold is washed, and the silver precipitated from the washings as silver chloride, by salt addition.

Zinc Concentrates

Zinc sulfide concentrates are roasted and leached with sulfuric acid. The sulfuric acid leach dissolves the majority of the zinc, leaving 5-10% in the residue, along with the impurities of gold, lead, and silver. This rese is melted to form a slag, and powdered coal or coke is blown into the melt along with air, a process known as slag fuming. Zinc is reduced and vaporized from the slag; the lead is converted to its metallic form and dissolves the silver and gold. The metallic lead bullion is collected and refined, such that high-purity silver can be recovered using the Parkes process described above.

Silver Recycling

Over 60% of silver used globally in 2024 was for industrial fabrication, which includes the photographic industry, as well as EEEs. Just over 20% of silver was used in jewelry & silverware manufacturing.2 In the photographic industry, silver can be recycled from spent photographic processing solutions via electrolytic methods. In the jewelry industry, high-grade jewelry scrap can be re-alloyed and the silver recycled on-site. The process includes collecting the fine dust that is generated when precious metals are polished and ground, known as the ‘jewelry sweeps’. The dust is smelted and electrorefined to obtain pure silver. Often, low-grade silver scrap has very low value, and is returned to a smelter to be processed. Methods that are applied to gold recycling, such as cyanidation, are not usually economical for silver scrap.

Silver Electrorefining and Silver Purification

Silver can be refined through electrolysis, using anodes made up of crude silver and gold: approximately 60% silver, 30% gold, and the remaining 10% as base metals. The anodes are made by charging silver and gold bullion into a furnace, the same furnace that is used for melting fine silver and gold to be cast into bars. The cathodes used in silver electrolysis are thin sheets of 1000 fine silver, crystallized silver powder collects on the cathodes and removed by knocking or sweeping the cathodes. The silver powder is washd in a centrifuge to free the metal from the soluble impurities and acid. This powder is then melted down into bars. The electrolyte in this process is made up of 3% silver, in the form of silver nitrate, 1.5-2% free nitric acid, and a little liquid glue, with the purpose of toughening the silver deposit on the cathode. If the electrolyte has greater than 8% copper it will also deposit onto the cathode, which is why the silver concentration must be monitored in the electrolyte. To prevent the silver from sticking to the cathodes, the cathode sheets are treated with a “dopvee” which consists of silver nitrate, copper nitrate, and hydrochloric acid. The anodes are removed when the silver has been depleted to ~10% of the anode, which is now crude or “black” gold, containing approximately 1% base metals. The anodes are melted down and ready for gold electrolysis.

Silver Electrowinning

Electrowinning of silver is another effective method for silver purification and silver recovery, especially directly from solutions containing silver. Examples of this include solutions from the photographic industry, or in the recycling of photovoltaics.

As described in the section on gold concentrates, gold and silver are precipitated from solution using zinc, in the Merrill-Crowe process, based on their nobility. Being more noble, they have a preference to remain in their metallic states. Ag(I) has a reduction potential of 0.8V; Au(I) of 1.7V. Based on the same principle of reduction potential, gold and silver can also be easily electrowon from solution into high-purity products.

Electrowinning with emew technology, silver can be recovered to a purity of up to 99.999%, even in the presence of base metals. Impurities such as cadmium, copper, lead and others are easily rejected. With emew polishing cells, the electrolyte can be depleted to <10 ppm.

Advantages of emew technology include the ability to recover high-purity silver from many different solutions:

- Caustic cyanide PLS

- Nitric acid electrolyte

- Refinery by-products

- Bleed streams

- Effluent streams

- Low-grade waste materials

- Scrap silver and shredder residues

- Plating baths

A large precious metals refinery in India produces over one tonne per day of high-purity silver using emew technology. With emew’s high surface area cathode, they also deplete silver in the electrolyte to less than 5ppm and eliminate silver chloride precipitation on the bleed to effluent treatment.

Direct electrowinning can be used on a wide range of electrolytes containing silver. With emew technology, 99.99% silver can be produced from an electrolyte with as low as 10 g/L silver, giving a distinct and obvious advantage over conventional silver refining. Table 1 below outlines the primary differences between electrorefining and emew electrowinning of silver.

Table 1: Conventional Electrorefining vs. emewPowder Technology for Silver Recovery

Future Outlook on Silver Recovery

Recovery of silver and silver recycling is accomplished using various methods, including the Parkes process, cupellation, parting, slag fuming, and electrolysis (electrorefining and electrowinning). Silver is most often recovered from low-grade mineral ores, with less than 2% silver content. The techniques mentioned above, while employed for silver recovery from ores, can also be utilized for silver recovery from EEEs, including solar panels and circuit boards. Recycling of silver from these EEEs will be a very important area for the future, as metal demands increase with new technological advancements. In the U.S., it was quoted by Lazard that new solar power plants are now cheaper than new coal, natural gas, or nuclear power plants, and the price continues to drop. In Australia, China, India, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, costs are dropping even faster. With so much growth in the industry, it means that there will be a need for more solar panel recycling in the coming years.

Research continues to show high recovery efficiencies for silver and copper from spent solar cells, with recent techniques achieving up to 98.7% efficiency. While standard silicon modules have historically contained lower amounts, an average contemporary solar panel is now reported to contain approximately 20 g (0.7 oz) of silver. At a 98% recovery rate, 19.6 g (0.63 ozt) of silver per module at the 2024 average price of $28.27 USD/ozt equates to approximately $17.81 USD/module.

The global market for solar PV recycling was valued at approximately $492.8 million USD in 2024 and is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 19.7% through 2034. With silver demand in the photovoltaic (PV) sector reaching record highs of 197.6 Moz in 2024, recycling will be essential to sustain the "green economy" as older panels reach their 25-30 year end-of-life.2

The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) reported in January 2025 that known global silver reserves have increased to 640,000 metric tons. In 2024, global mine production reached 819.7 million ounces (Moz), which is approximately 25,500 metric tons. At this current rate of extraction, identified global reserves would theoretically last for roughly 25 years. However, the Silver Institute notes that 2025 will mark the fifth consecutive year of a significant market deficit, totalling nearly 800 Moz (25,000 t) over the 2021–2025 period. Harnessing the power of emew technology for silver recovery from a variety of silver-containing ores and WEEEs will help supply high-grade silver to meet the demand in the years to come. Following cyanide leaching, or other ore concentrate leaching processes, bleed solutions can be run through an emew system to recover silver from a wide range of silver concentrations. For more information on the power of emew for silver recovery, and various case studies, please visit the Downloads section on our website.

Sources:

- https://silverinstitute.org/silver-demand-forecast-to-expand-across-key-technology-sectors/

- https://silverinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/World_Silver_Survey-2025.pdf

Other sources:

Adams, Mike D. (2005). Advances in Gold Ore Processing. Elsevier. pp. XXXVII–XLII.

https://asu.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/a-process-to-recover-silver-from-silicon-solar-cells

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/7750344

https://www.britannica.com/technology/silver-processing

https://www.denvermineral.com/merrill-crowe-systems/

https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/solar-panel-recycling-market

http://www.mine-engineer.com/mining/minproc/cyanide_leach.htm

https://www.revolvy.com/main/index.php?s=Parkes%20process

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0927024816001227

https://silverinstitute.org/silver-catalysts/

https://www.silverinstitute.org/silver-in-electronics/

https://www.silverinstitute.org/silver-solar-technology/

https://www.thebalancesmb.com/an-introduction-to-metal-recycling-4057469

https://www.911metallurgist.com/blog/electrolytic-refining

Industrial Process Profiles for Environmental Use, Volume 168. (1980). Cincinnati: Industrial Environmental Research Laboratory, Office of Research and Development, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Lazard's levelled cost of energy analysis. (2016). 10th ed. [ebook] Lazard. Available at: https://www.lazard.com/media/438038/levelized-cost-of-energy-v100.pdf [Accessed 8 Dec. 2017].

Leong, W.W. and Mujumdar, A.S. (2009). Gold Extraction and Recovery Processes. [pdf] Singapore: National University of Singapore. Available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7559/67e38c3b788c9d41aaedec4f3d5ebd921855.pdf [Accessed 8 Dec. 2017]

Percy, J. (1870). The metallurgy of lead. London: J. Murray. pp. 148

U.S. Geological, Survey Mineral, Commodity Summaries, 2015.

Wiebe, J. (2017). Silver Survey Update 2017. [ebook] Thomson Reuters. Available at: https://www.silverinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/SilverMarke-2017_Interim.pdf [Accessed 8 Dec. 2017].

World Silver Survey, 2015.